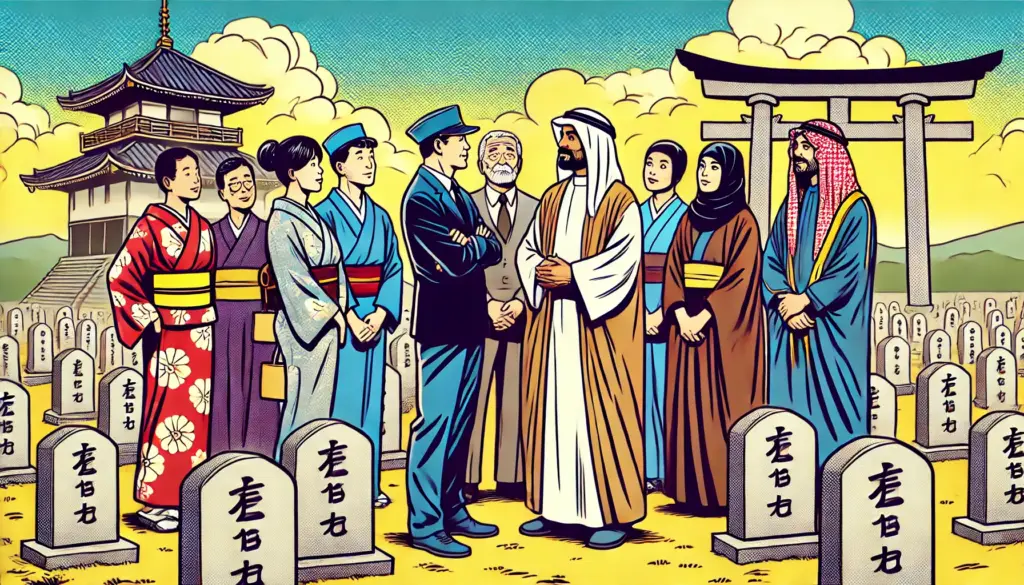

In Japan, certain everyday Japanese terms that used to be widely accepted are now seen as outdated or politically insensitive. While they were natural in speech before the early 2000s, shifts in social awareness and inclusivity have made them inappropriate in today’s context. Below are some notable examples, presented as: Japanese word, Romanization, and literal English translation.

Examples of Deprecated Terms

- 肌色 / Hada-iro / skin color

- 床屋 / Tokoya / barber’s shop (male-focused)

- 看護婦 / Kangofu / female nurse

- 保母 / Ho-bo / female child-minder

- スチュワーデス / Suchuwādesu / stewardess

By the early 2000s, these were replaced: 看護師 (kangoshi) replaced 看護婦, 保育士 (hoiku-shi) replaced 保母, and 客室乗務員 or キャビンアテンダント replaced スチュワーデス.

Why Were These Terms Changed?

1. Gender Inclusivity ✨

Terms like 看護婦 or 保母 explicitly referred to women, reflecting a time when these roles were seen as inherently female. As society moved toward gender equality, gender-neutral terms such as 看護師 and 保育士 were adopted to include all genders.

2. Global Influence & Political Correctness

Following global trends in political correctness, Japanese society reviewed expressions to remove implicit bias. Although political correctness originated in Western discourse in the 1970s–80s, its framework began to influence Japanese language usage around the turn of the millennium.

3. Institutional & Legal Changes

By law and policy, terms like 保母 officially changed in 1999, and 看護婦 by 2001, reflecting formal recognition that language shapes perception and inclusivity.

Broader Shifts in Japanese Terminology

Beyond these occupational terms, other words faded due to changing norms:

- 肌色 (Hada-iro, skin color) once denoted a light peach shade for stationery or web design. However, as society explored racial diversity, it became problematic and largely replaced by terms like ベージュ系 (“beige-tone”).

- 床屋 (Tokoya) specifically implied a male barber shop, often excluding female customers or hairdressers. Now more general terms like 理容室 or ヘアサロン are preferred.

Although not always legally mandated, such shifts reflect greater societal mindfulness about language’s role in representing inclusion.

My Take: Why Language Matters

Language isn’t merely descriptive—it shapes how we perceive roles and identities. When a term like 看護婦 implies “female-only”, it subtly reinforces gender stereotypes. Updating to 看護師 or 保育士 doesn’t just change words—it signals who belongs, and who is visible in public life.

Yet some changes feel overly rigid. Eliminating 床屋 may make sense formally, but in rural Japan many people still say it colloquially. The balance between preserving everyday speech and promoting inclusive language is a complex cultural negotiation.

How to Approach Politically Sensitive Language Today

- Aim for gender-neutral terms when referring to occupations or roles.

- Stay informed: guidelines can evolve—e.g. 母子手帳 became 親子手帳 to include father participation.

- Consider audience and context: in casual settings older terms might still appear, but professional content benefits from inclusive language.

Summary Table

| Japanese Term | Romanization | Literal English | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 肌色 | Hada-iro | Skin color | ベージュ系 (beige-tone) |

| 床屋 | Tokoya | Barber shop | 理容室、ヘアサロン |

| 看護婦 | Kangofu | Female nurse | 看護師 (kangoshi) |

| 保母 | Ho-bo | Female caretaker | 保育士 (hoiku-shi) |

| スチュワーデス | Suchuwādesu | Stewardess | 客室乗務員, キャビンアテンダント |

Final Thoughts 😊

Language evolves with society. Terms that once felt harmless may, over time, carry unintended bias. As writers, educators, and communicators, choosing inclusive expressions not only reflects awareness but actively helps foster a culture of equality. It doesn’t erase history—it enriches it, by acknowledging all voices.