Introduction: When Dialects Go Mainstream

Once considered markers of regional identity, certain words from the Kansai dialect (Kansaiben)—such as “めっちゃ” (meccha) and “しんどい” (shindoi)—have spread across Japan and become part of everyday vocabulary even in Tokyo and beyond. What caused these regional expressions to lose their local flavor and gain national popularity? The answer lies in a fascinating blend of media influence, shifting cultural attitudes, and the irresistible charm of Kansai-ben itself 🎤🇯🇵

Section 1: What Is Kansai-ben, and Why Was It Regional?

Kansai-ben refers to the set of dialects spoken in the Kansai region, including Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe. Known for its expressive tone, rhythmic cadence, and punchy delivery, Kansai-ben has long been associated with comedy, warmth, and assertiveness.

For decades, Kansai-ben was just that—regional. People from Tokyo or other parts of Japan often viewed it as too casual, too emotional, or even “unrefined” for public or professional use. Many Kansai natives moving to Tokyo found themselves switching to standard Japanese (標準語) in order to fit in.

But something changed.

Section 2: The Breakout Words — “Meccha,” “Shindoi,” and More

Let’s look at a few iconic words that were once uniquely Kansai but are now heard everywhere:

- めっちゃ (meccha)

Originally a Kansai intensifier meaning “very” or “super,” it replaced standard terms like とても (totemo) or すごく (sugoku) in casual speech.

*Example: “めっちゃかわいい!” (Super cute!) - しんどい (shindoi)

Once rarely used outside Kansai, this word expresses physical or mental exhaustion and is now widely used instead of the more formal つかれた (tsukareta).

*Example: “昨日の仕事、しんどかった…” (Yesterday’s work was so tiring…) - なんでやねん (nande yanen)

This classic comedic retort—“What the heck are you talking about?”—remains closely tied to Kansai culture but is recognized and mimicked across Japan, especially thanks to manzai comedy. - あかん (akan)

A strong word meaning “no good” or “don’t,” now used casually even by non-Kansai speakers for emphasis.

*Example: “それ、あかんやろ!” (That’s not okay!)

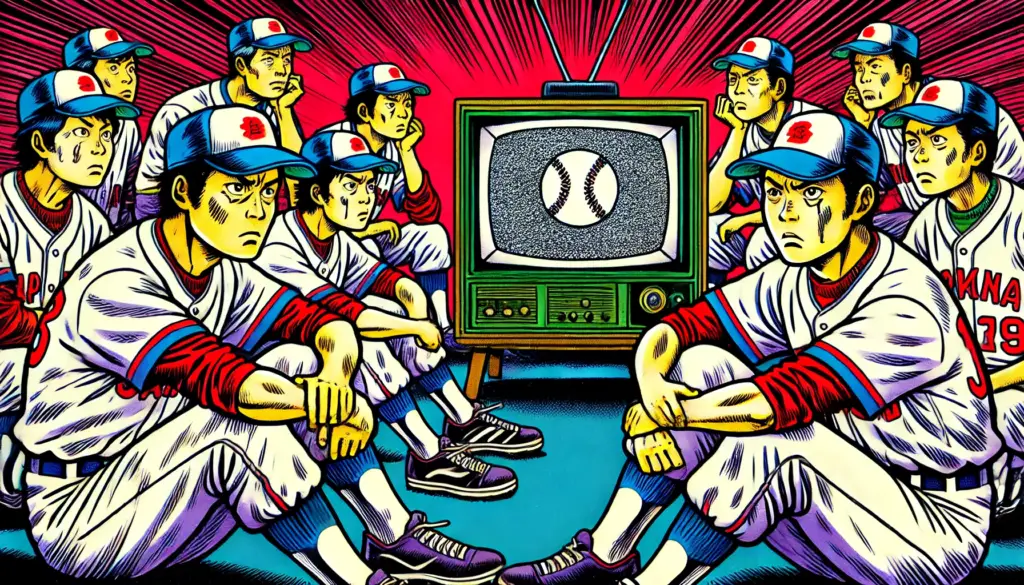

Section 3: Media Power — The Role of Comedy and TV

A major reason these words gained traction outside of Kansai is the dominance of Kansai-based entertainers in Japanese media.

- 吉本興業 (Yoshimoto Kogyo), the entertainment company behind countless popular comedians, helped normalize Kansai-ben nationally. Manzai duos like Downtown (ダウンタウン), Ninety-Nine, and more brought their local dialect to primetime TV, influencing how young people speak across Japan.

- Variety shows, a staple of Japanese entertainment, often feature Kansai-native comedians who use casual, witty language. The frequency of these expressions on screen made them sound more “normal” and less regional.

- Anime and manga also contributed. Characters using Kansai-ben—like Kansai-dialect Pikachu in special episodes, or comic relief characters in popular series—made these phrases fun and memorable.

Section 4: Social Shifts — Embracing Informality and Identity

Another reason for this linguistic diffusion is a shift in Japanese culture toward casual expression and individuality.

- In the past, speaking “correctly” (i.e., using 標準語) was associated with professionalism and urban sophistication. But younger generations began favoring expressions that felt more real, emotional, and punchy.

- Kansai-ben offers that: a sense of authenticity. Saying “めっちゃ楽しい” feels more expressive than “とても楽しい.”

- Additionally, the rise of SNS and YouTube has allowed dialects to thrive. YouTubers from Osaka, TikTok users from Kobe, and Instagrammers from Kyoto use their local language—and audiences across Japan are picking up the lingo.

Section 5: Kansai-ben as Pop Culture, Not Just Dialect

What was once a matter of geography has now become a form of pop culture branding:

- Brands use “めっちゃ” in advertising slogans to appear fun and relatable.

- Young Tokyoites deliberately pepper their speech with Kansai terms to seem approachable or funny.

- Fashion brands, cafes, and social media influencers embrace Kansai flair as a quirky, nostalgic, or comedic identity.

Just like how English speakers might borrow from slang in TV shows or hip-hop, Japanese youth have started to treat Kansai-ben like a “cool dialect”—something to adopt, remix, and make their own.

Section 6: Is Kansai-ben Losing Its Identity?

As words like “meccha” and “shindoi” become nationalized, some in the Kansai region feel a sense of linguistic dilution. These words were once intimate signifiers of cultural belonging, and now they’re just trendy slang.

Yet, it’s also a kind of victory. Kansai culture—often seen as the underdog to Tokyo’s dominance—has left a permanent mark on Japanese society.

Rather than disappearing, Kansai-ben is evolving. Its core expressions live on, traveling far beyond the streets of Osaka, yet always carrying a trace of their origins.

Conclusion: From Local to Global (Within Japan)

The journey of words like “めっちゃ” and “しんどい” reflects a larger story about language, identity, and media influence. Kansai-ben has gone from being a regional accent to a cultural force. And while the lines between dialects blur, what remains is the joyful, expressive heart of Kansai.

So next time someone says “Meccha shindoi…” you’ll know: that’s not just tired—it’s Kansai tired 😄💬