In Japan, McDonald’s has long positioned its Happy Meal (known locally as “Happy Set”) as a family-oriented product: an affordable meal bundled with limited-edition toys that excite children and attract collectors. However, the system recently faced a major challenge. On August 20, McDonald’s Japan announced the suspension of the planned One Piece Happy Meal campaign, citing concerns over rampant resale activity and food waste.

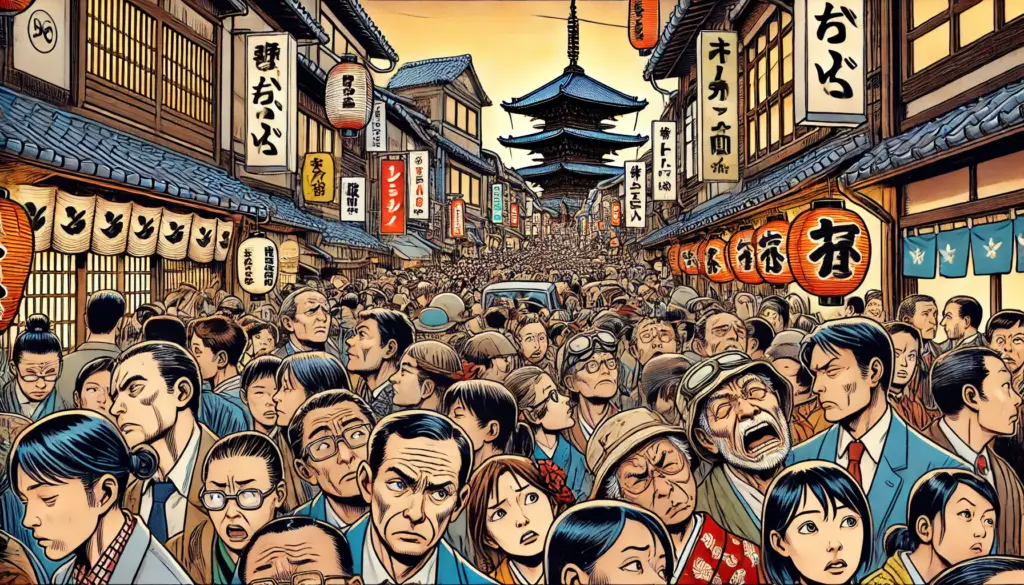

This cancellation, originally scheduled to begin on August 29, came after chaos surrounding the Pokémon Happy Meal earlier in the month, which saw enthusiastic fans and profiteers overwhelming stores nationwide.

What Happened with the Pokémon Happy Meal?

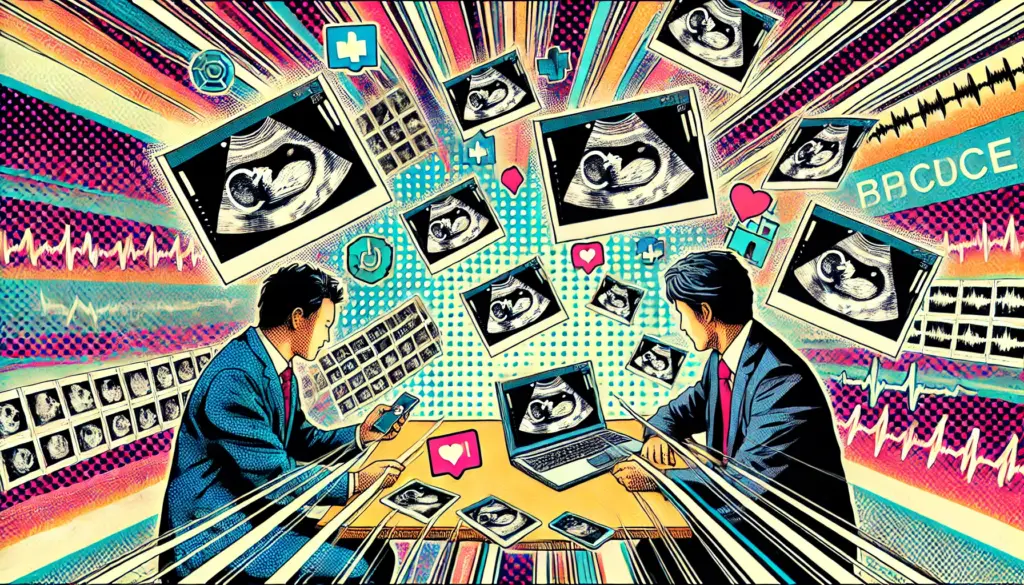

From August 9 to 11, McDonald’s released a special Pokémon Happy Meal that included figures such as Pikachu and Charmander, along with exclusive Pokémon trading cards. These cards proved irresistible not only to young fans but also to adult collectors and resellers seeking to profit online.

The result was mayhem:

- Many customers purchased dozens of meals solely to obtain cards.

- Within the first day, Pokémon cards were already unavailable at multiple outlets.

- Social media filled with complaints about children being unable to get the toys.

- Photographs of discarded untouched meals highlighted the problem of food waste caused by bulk buying.

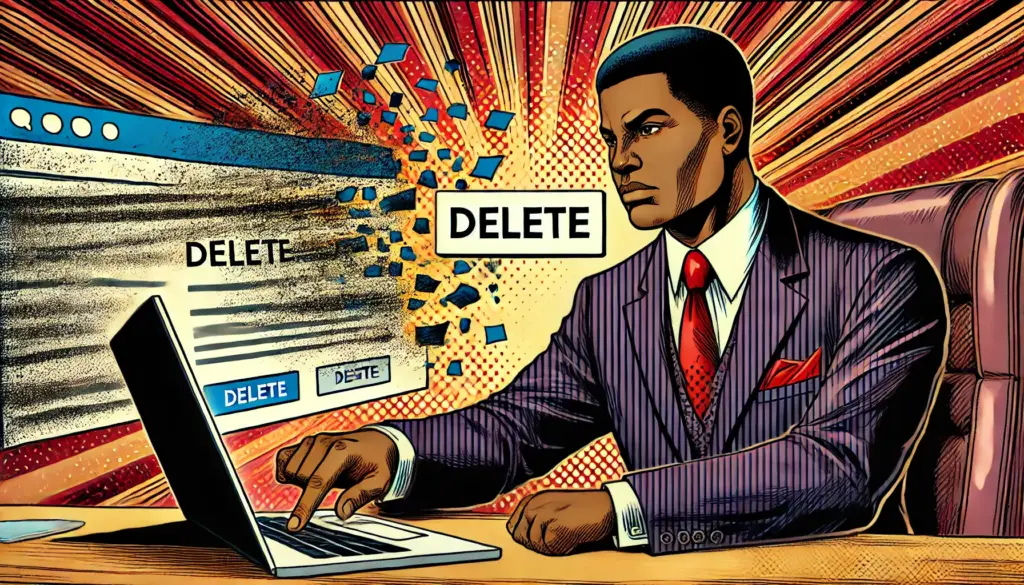

By August 11, McDonald’s Japan issued an apology, stating: “We sincerely apologize for the significant inconvenience caused. We do not condone the resale-driven purchase of Happy Meals, nor the waste of food products.” The company also promised stricter countermeasures, including purchase limits per customer.

Why the One Piece Campaign Was Stopped

The One Piece Happy Meal campaign was supposed to feature limited-edition trading cards from the One Piece Card Game, a franchise that has surged in popularity both domestically and internationally. Given the frenzy over Pokémon, McDonald’s feared history would repeat itself:

- High demand from resellers leading to shortages.

- Uncontrolled crowds at stores.

- The potential for unsold food being discarded after bulk purchases.

Instead of the One Piece collaboration, McDonald’s announced it would offer re-released toys from past Happy Meal campaigns during the scheduled period. While this substitution disappointed many fans, it reflected a strategic decision to prioritize safety, fairness, and food sustainability.

The Bigger Picture: Resale Culture in Japan

Japan has a deeply entrenched resale culture, spanning sneakers, concert tickets, and trading cards. Platforms like Mercari and Yahoo Auctions allow individuals to flip limited-edition goods at a premium. While resale itself is not illegal, its side effects are increasingly under scrutiny:

- Children and families lose access to affordable collectibles, the original target audience.

- Prices inflate dramatically online, turning a ¥500 meal toy into a ¥5,000 resale item.

- Food waste rises when meals are purchased for the toy alone.

- Staff and customers face confusion during chaotic release days.

The Pokémon Happy Meal controversy was just the latest example of how resale culture collides with mass-market promotions.

McDonald’s Japan’s New Strategy

Going forward, McDonald’s Japan announced plans to strengthen Happy Meal sales regulations:

- Tighter limits on how many meals one customer can buy.

- Improved inventory distribution across outlets to prevent early shortages.

- Enhanced messaging against resale practices.

The company is now in a delicate position—balancing its role as a family-friendly brand while navigating the collector-driven demand that fuels both popularity and chaos.

What This Means for Fans

For fans of One Piece and Pokémon, the cancellation was bittersweet. On one hand, the decision prevented another chaotic rush. On the other, it deprived children of a rare crossover moment between McDonald’s and one of Japan’s biggest franchises.

Yet the controversy highlights a broader question: should companies continue producing limited-edition goods when resale culture dominates the outcome? For McDonald’s, this may push future collaborations toward digital rewards, lotteries, or pre-order systems rather than mass distribution at physical stores.

Conclusion

The suspension of the One Piece Happy Meal shows how resale-driven demand can disrupt family-oriented promotions, turning a cheerful campaign into a public-relations challenge. While McDonald’s Japan acted preemptively this time, the incident underscores a growing dilemma for global brands: how to protect the spirit of accessibility while facing the realities of speculative resale markets.

In the end, this episode may mark a turning point in how Japanese fast-food chains—and perhaps brands worldwide—handle limited-edition promotions in the age of online reselling.