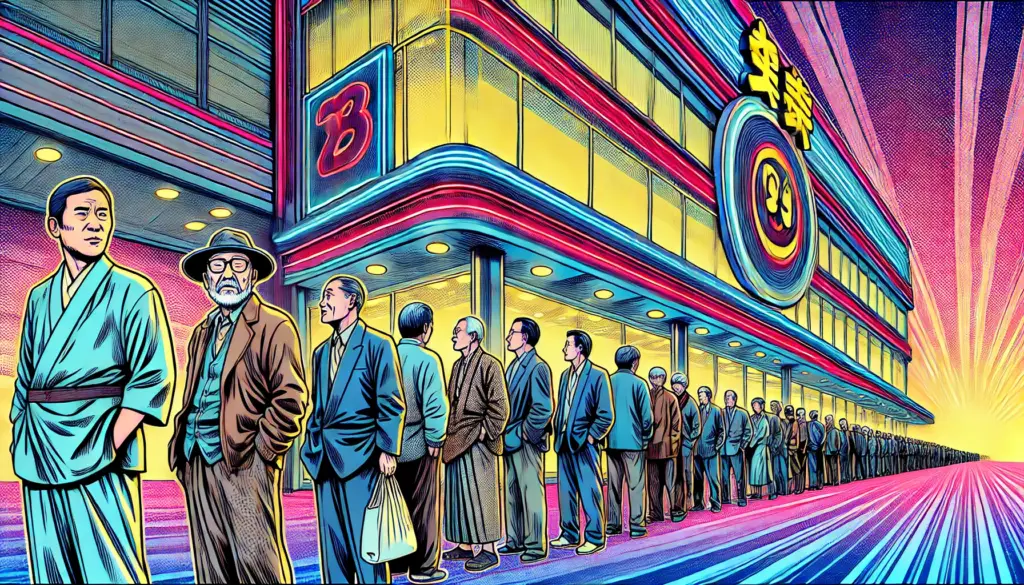

Every month in Japan, something curious happens. On certain days, crowds begin to gather at very specific entertainment venues — not for a concert or sale, but for a regular activity that’s as routine as the calendar itself. These gatherings seem to follow a rhythm tied not to weather or holidays, but to bank deposits.

At the center of this monthly surge is a powerful and often overlooked force: government assistance payments. While these funds are meant to help people in need, their sudden release into society also fuels a hidden corner of Japan’s domestic economy — with serious social and ethical implications.

The Curious Timing of the Crowds

In many cities, entertainment venues experience a sharp increase in foot traffic in the first few days of the month. This aligns precisely with the deposit schedule of public support payments. Individuals who rely on these funds often receive them between the 1st and 5th of each month, depending on local policies.

Almost like clockwork, these individuals — now with cash in hand — head to their preferred places for leisure, leading to sudden lines and packed entrances. Business owners are aware of this pattern and often adjust their operations accordingly.

It’s no coincidence — it’s a cycle.

No Laws Against Spending Choices

Japan’s laws do not restrict how public assistance funds are spent. Recipients are expected to use the money for essential living expenses such as food, housing, and utilities. However, there is no legal prohibition on using the funds for non-essentials, including leisure activities.

This legal freedom creates a grey area. On the one hand, people receiving assistance are legally entitled to a minimum standard of living, which includes the freedom to enjoy life. On the other, the public often questions whether it’s appropriate for those receiving public support to engage in entertainment spending that appears excessive or risky.

The controversy intensifies when the entertainment involves the potential for financial loss.

A System That Disincentivizes Winning

What many don’t realize is that when public assistance recipients earn money — even small amounts — that income must be reported. Any “winnings” can directly reduce their next payment. For instance, someone who gains 20,000 yen through leisure activities may see a similar reduction in future support.

This system ironically penalizes success and rewards status quo. People who lose money remain eligible for assistance, while those who gain anything risk having their support withdrawn or reduced. In practice, it creates a strange incentive to continue spending without ever improving one’s financial situation.

This feedback loop keeps some recipients locked in a cycle, always returning, always spending — but never truly getting ahead.

Who Benefits Most?

Interestingly, businesses that provide these forms of leisure often see their highest revenues around public payment dates. Owners prepare for the rush, anticipating regular and reliable traffic. The first week of the month becomes a kind of unofficial harvest period for these venues.

This pattern means that a portion of government aid meant for personal well-being ends up in the hands of private enterprises. It’s not illegal — it’s not even necessarily unethical — but it raises a question: is the system truly serving those it’s meant to help?

A Vulnerable Audience

For individuals under financial stress, leisure offers a brief escape from the pressures of life. Many recipients of government aid are isolated, unemployed, or struggling with mental health. Entertainment becomes one of the few accessible ways to experience joy or hope.

But that very accessibility can turn into dependency. Some people develop unhealthy habits — spending beyond their means, returning again and again for fleeting highs. Without strong social safety nets or emotional support, these venues become a kind of default coping mechanism.

Unfortunately, entertainment that costs money can quickly become harmful to people who don’t have much to lose in the first place.

Social Tensions and Public Expectations

The public often reacts with frustration. Many people believe government assistance should be used exclusively for essentials like food and shelter. When photos or anecdotes emerge of people spending their benefits on leisure, public trust in the welfare system can decline.

Some municipalities have even attempted to monitor or restrict how recipients spend their funds, sparking fierce debates over privacy and human rights. But without legal backing, these measures usually fail — and may even discourage people from seeking help in the first place.

The line between freedom and responsibility becomes blurred.

Why the Cycle Continues

Several structural issues reinforce this cycle:

- Timing of Payments: Receiving a lump sum at the start of the month creates a strong psychological urge to spend.

- Lack of Restrictions: There are no mechanisms to guide or limit how funds are used unless abuse is proven.

- Social Isolation: Many recipients lack access to healthier leisure options or community activities.

- Policy Gaps: Winning is discouraged, but losing has no penalty — unintentionally creating a safe space for failure.

It’s a silent system. One that quietly turns public funds into private gains every single month.

What Can Be Done?

There is no easy solution, but some possibilities include:

- Integrating financial education with government assistance programs

- Offering counseling for those struggling with money-related addictions

- Creating more accessible leisure alternatives, such as community centers or free events

- Establishing voluntary exclusion systems for at-risk individuals who want help avoiding harmful spending

- Improving transparency without invading privacy, so public trust in support programs remains strong

These ideas don’t eliminate the core issue — but they empower individuals to make more sustainable choices.

Final Thoughts

The monthly rush that forms on public payment days is not just a quirk of the calendar. It reflects deep systemic challenges: how assistance is distributed, how it is perceived, and how it interacts with vulnerable populations.

At the heart of it is a tension: between the right to live with dignity, and the responsibility to use that support wisely.

Until better safeguards and broader support systems are in place, this cycle — of giving, spending, losing, and returning — will likely continue, month after month.