While climate change dominates political debates in Europe, it remains a secondary concern in Japanese elections. Why is this the case? Let’s explore the cultural, political, and structural differences between Japan and European democracies—and what might change in the future. 🌏

🗳️ Japanese Voters Prioritize Everyday Life Over the Environment

In surveys conducted by Japanese media outlets such as NHK and Yomiuri, climate change consistently ranks lower than issues like:

- Inflation and consumer prices 💸

- Social security and pensions 👵

- Childcare and education support 🧒

- Economic growth and job security 📉

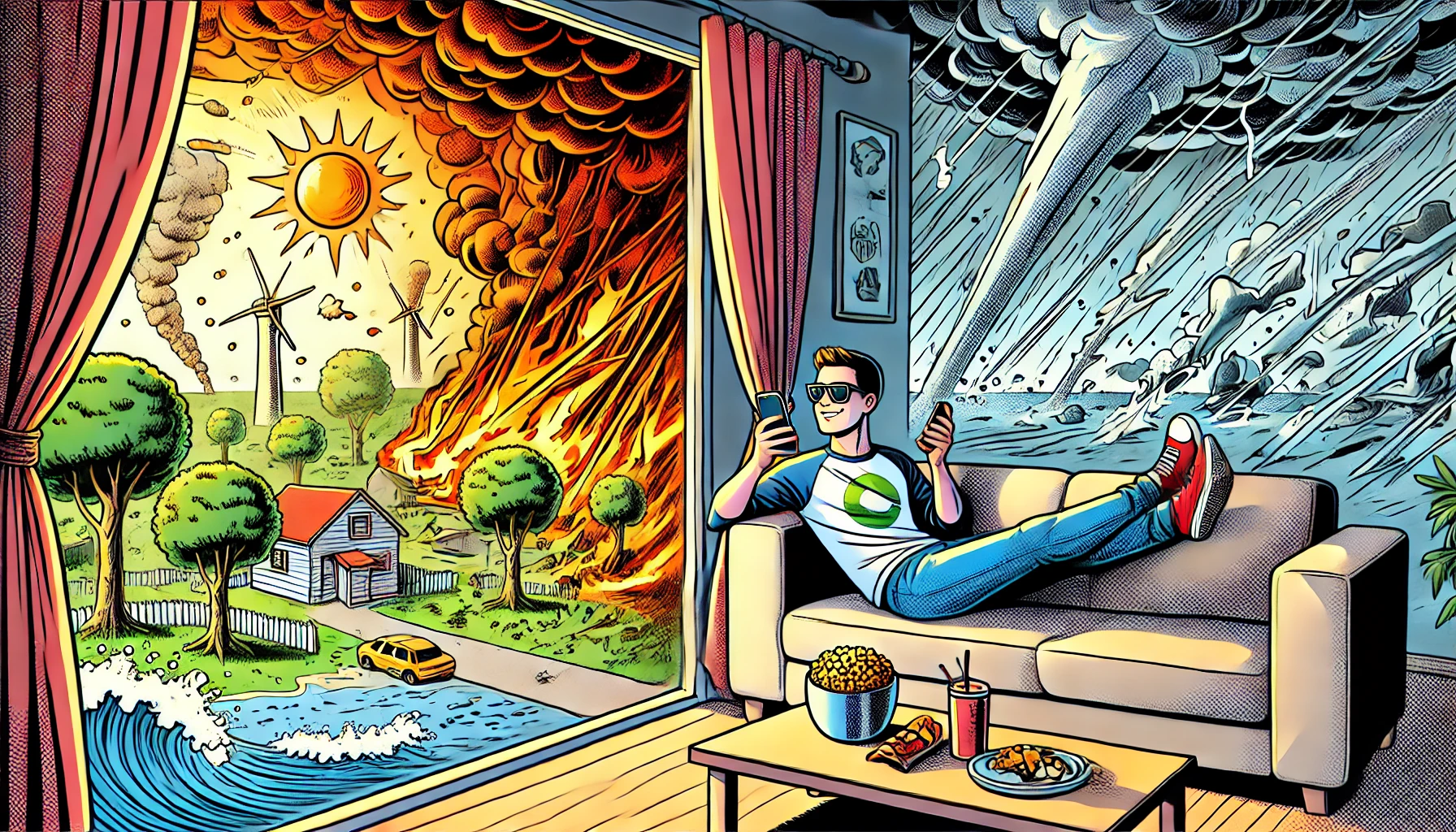

Despite frequent extreme weather events in Japan—such as deadly heatwaves and typhoons—voters often don’t connect these to climate policies. The sense of urgency seen in Europe hasn’t fully translated into voting behavior.

🏛️ Political Parties in Japan Avoid Confrontation on Climate

Unlike in Europe, where political parties often clash over climate strategies, Japan’s ruling and opposition parties show minimal ideological differences on environmental issues.

- The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Japan’s ruling party, has pledged carbon neutrality by 2050, but progress has been slow.

- Opposition parties like the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) and Japan Innovation Party (Ishin) support climate action but don’t strongly campaign on it.

- With little contrast between platforms, voters see climate change as a background issue—important but not decisive. 🎭

In short: there’s no clear “climate party” like Germany’s Greens or France’s EELV to rally around.

🧠 Cultural and Media Factors Also Play a Role

Japan’s political culture emphasizes consensus, harmony, and gradualism. This makes it hard to push radical reforms—even when needed.

- Japanese media often treat climate change as a global problem rather than a national crisis 🌍

- Public discourse rarely links climate policies with personal benefits like energy savings or public health 🏥

- Climate activists in Japan are few in number and face social resistance when challenging the status quo 🧏

🇪🇺 In Europe, Climate Is a Ballot Box Issue

European voters are more engaged with climate politics for several reasons:

- Green parties hold real power and often participate in coalitions 🟢

- Climate-related protests like “Fridays for Future” and Extinction Rebellion mobilize youth 📣

- The EU mandates national-level climate targets, pushing governments to act 📊

For example, Germany’s Green Party played a major role in shaping energy and transport policy after the 2021 election. In France, climate policy was central to presidential debates. Such developments remain rare in Japan.

📉 Lack of Youth Impact in Japan

Although many young Japanese people care about climate change, their political influence is limited:

- Japan has one of the lowest youth voter turnout rates in the developed world 🚫🗳️

- Climate activism is less visible and less organized than in Europe 🪧

- School curriculums include climate topics but not civic engagement strategies 📚

Without a louder youth voice, climate issues struggle to break through the political noise.

🔮 What Could Change in the Future?

| Change Needed | Description |

|---|---|

| 🎯 Clearer Party Differentiation | Parties should adopt bold, visible climate policies and make them election priorities. |

| 🧩 Public Awareness Campaigns | Connect environmental issues to real-life challenges like rising electricity bills and disaster risks. |

| 🚀 Support Grassroots Movements | Encourage citizen groups, students, and NGOs to take active roles in policymaking. |

| 👥 Media Responsibility | Mainstream news should cover climate not just as science—but as politics, economy, and daily life. |

📝 Conclusion

As of July 2025, Japan still lags behind Europe in making climate change an electoral priority. While awareness is growing, especially among youth, political parties, media, and civil society must do more to elevate the issue.

For Japan to meet its carbon neutrality goals—and for voters to have real influence—climate change must become more than a policy promise. It needs to become a political demand.