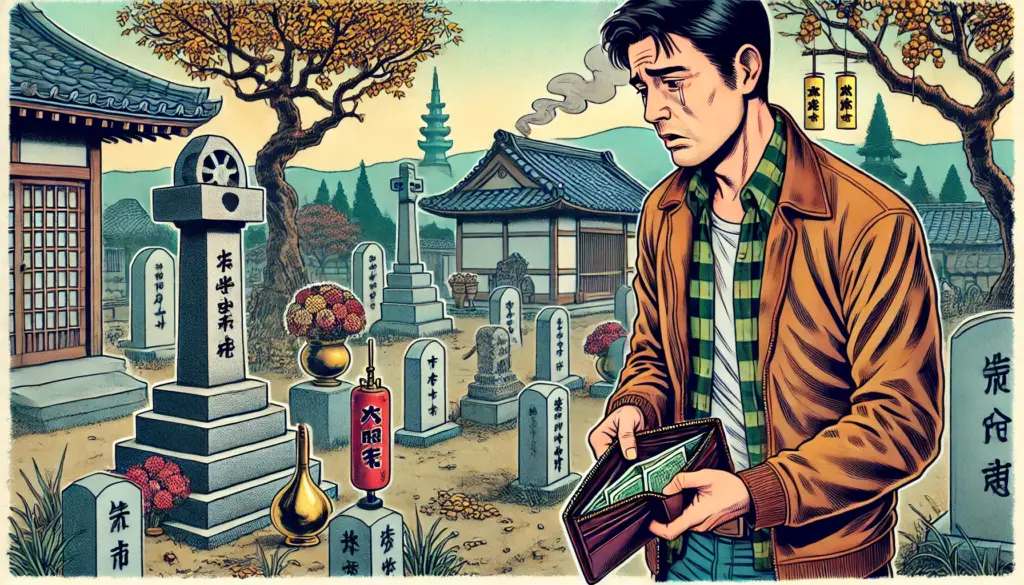

In Japan, death has long been treated with reverence, tradition, and ritual. But in recent years, one sobering reality has begun to surface: dying in Japan now costs more than many people can afford. Funeral expenses, ancestral graves, temple fees, and ongoing memorial rituals have turned the simple act of passing away into a financial burden for both the living and the dead. This issue, once quietly whispered about, is now drawing public attention—and for good reason.

As of July 27, 2025, surveys and media reports suggest that even middle-class families are struggling to afford the “cost of dying”, while younger generations feel trapped between tradition and reality.

💸 The True Cost of Death in Japan

A standard Japanese funeral often includes the following components:

- Wake (tsuya)

- Funeral ceremony (sōshiki)

- Cremation

- Grave or columbarium purchase

- Ongoing memorial services

These costs combined typically range between ¥2 million to ¥3 million (approx. $13,000–$20,000 USD). Here’s a breakdown:

| Item | Approximate Cost |

|---|---|

| Funeral ceremony & wake | ¥800,000 – ¥1,500,000 |

| Cremation | ¥70,000 – ¥100,000 |

| Grave plot (urban area) | ¥1 million – ¥5 million |

| Temple maintenance (per year) | ¥10,000 – ¥50,000 |

| Memorial services & offerings | Varies (over lifetime) |

While wealthier households may absorb this easily, single individuals, pensioners, and non-inheriting children increasingly cannot. It’s no longer rare to hear of people saying: “I can’t afford to die.”

⚠️ Why Is This Problem Surfacing Now?

1. Shrinking Families, Fewer Heirs

Japan’s declining birthrate has led to a severe shortage of family members who can maintain graves or cover funeral expenses. Elderly individuals often live alone, and many never married or had children. As a result, even the idea of passing on a family grave becomes unrealistic.

2. Collapse of Temple Support Systems

Traditionally, Buddhist temples managed and maintained family graves. However, with fewer donations and monks retiring, thousands of temples have closed across Japan in the past decade. When a temple closes, its graveholders must pay to relocate or face their ancestors becoming “muenbotoke”—souls without ties.

3. Urbanization and Grave Scarcity

As more people migrate to cities, urban cemeteries have become prohibitively expensive. In Tokyo, a small plot in a popular cemetery can cost as much as an apartment in the countryside. Even renting space in a columbarium (urn storage) inside a temple or building can cost hundreds of thousands of yen.

4. Cultural Pressure to “Do It Right”

Despite financial strain, many still feel obligated to conduct traditional Buddhist funerals and rituals, fearing judgment from relatives or neighbors if they opt for budget services. This emotional and societal pressure adds to the financial stress, especially during a time of mourning.

📉 What Happens If You Die With No Money?

Dying alone and impoverished in Japan may result in a “public welfare funeral” (seikatsu hogo sōshiki), handled by the local government. These funerals are basic and lack ceremonial elements. While they are free for the bereaved, many view them as shameful and undignified, despite growing demand.

There’s also the risk of “unclaimed remains,” where ashes are stored anonymously in mass graves or disposed of. In 2024 alone, Tokyo reported over 5,000 unclaimed cremations, a number that has doubled in the past decade.

🌱 New Alternatives for Dying with Dignity

Facing these rising costs and pressures, many Japanese people are choosing new, more affordable, and less traditional paths:

1. Direct Cremation (直葬 – Chokusō)

A minimal service that skips the wake and ceremony. It typically costs ¥100,000–¥200,000. More people are pre-arranging these plans while alive to avoid burdening their families.

2. Joint Graves (合同墓 or 永代供養墓)

These communal graves are offered by temples or municipalities and don’t require heirs for maintenance. Some include Buddhist prayers for the deceased in perpetuity. Costs can be as low as ¥30,000–¥300,000.

3. Tree and Ocean Burials (樹木葬・海洋散骨)

For those seeking eco-friendly or spiritual alternatives, ashes can be scattered at sea or buried beneath trees. These methods remove the need for expensive land plots and temple ties.

4. Digital End-of-Life Planning Services

“Shūkatsu” (終活, end-of-life preparation) platforms allow individuals to pre-plan their funeral, organize digital wills, and write “ending notes” (エンディングノート) for their families. This trend is particularly popular with childless elders and solo dwellers.

🧠 A Shift in Values: From Tradition to Practicality

Younger generations are increasingly prioritizing functionality and financial sanity over rigid tradition. Many now ask:

- “Why spend millions on a funeral I won’t even attend?”

- “Do I need a grave if my children won’t visit?”

- “Is it selfish to want a cheaper way out?”

These voices signal a deep cultural shift, where the meaning of mourning is evolving from material rituals to more personalized, minimalist expressions of respect.

📝 Final Thoughts

Japan’s aging population and economic shifts have revealed a profound truth: even in death, inequality persists. The inability to afford a “proper” death is pushing many into debt, guilt, or undignified ends. But with evolving norms and innovative solutions, a more humane, accessible way to die is emerging.

Dying shouldn’t require riches. It should require respect—and a society ready to honor the dead without bankrupting the living.